Artificial intelligence can, depending on who you ask, enhance or insult human-produced media such as music, visual art, movies, blogs and more. The conversation fluctuates from all perspectives. Many proponents on both sides often battle on the topic of human originality vs. technological advancement as well as the future of convenience vs. creation.

The thought of AI has always been an exciting concept, whether based on anxiety or sheer enjoyment. First entertained during the 1950s with the infamous Turing Test developed by mathematician and computer scientist Alan Turing to determine whether a machine is indistinguishable from a human, it was not much later in 1965 when AI pioneer and political scientist Herbert A. Simon said, “In twenty years, a machine will be capable of any work a man can do.”

Now, in the 21st century, we can see that Simon was not too far off in his prediction. There are automated machines on construction sites, robots serving food in restaurants and AI chat boxes to relieve the human need for connections (or perhaps to solve a problem on a homework assignment). Although odd, it is a fact that humans can feel emotionally attached to these insentient beings as if they were just rocks with googly eyes that people treated like live pets. But what about an emotional connection to an AI-generated piece of media? Can that happen in the same way a movie can make you cry or a stand-up comic can make you laugh?

“AI should help us create, not take our place,” Asiyah Burton (10) said. “It’s not a bad thing nor a good thing—I’m in the middle. To be honest, AI can take the creative world far beyond what I can imagine. Or it can damage the creative world.”

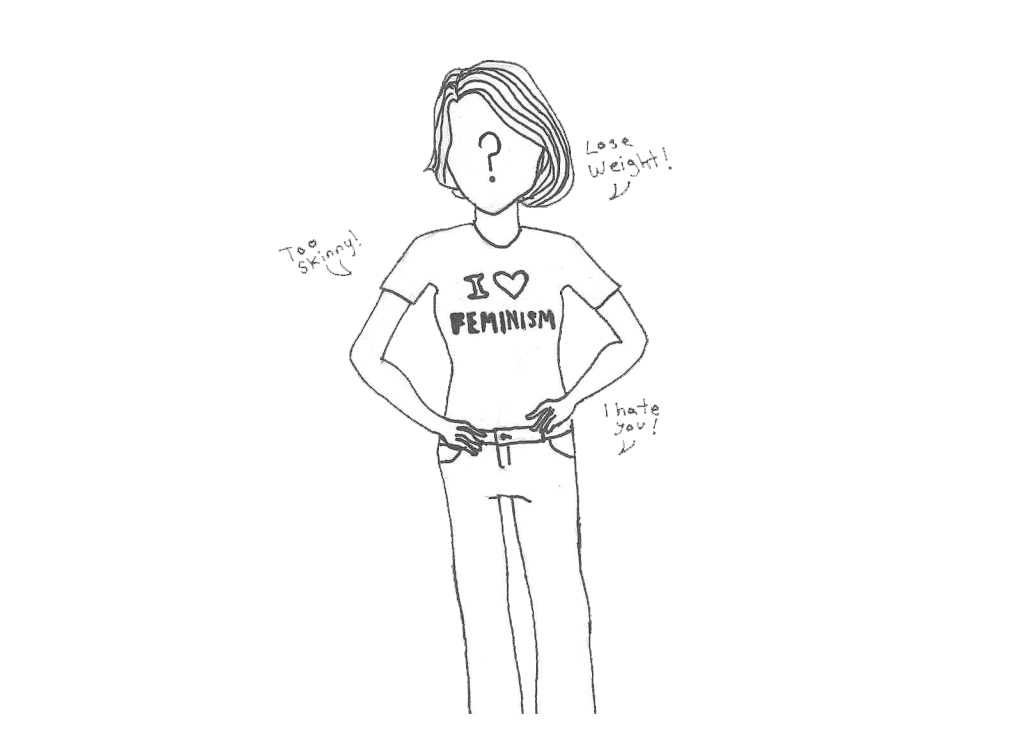

Maybe what its defenders see in what haters have dubbed “AI slop” is less about real connection and more about the human nature to love for things to be done for us as a service, rather than by us. But where does artificial intelligence use cross the line? If modern-day art is being created in a hurry with no incentive other than immediate gratification, can the audience truly enjoy it? If art is being created just to avoid true creativity and work, can it be truly enjoyed by respective fans? Many artists, especially ones with a history of acclaimed imagination and skill well before the inception of AI as we know it today, are confused and quite distasteful of this new era. These are the thoughts of Japanese co-founder and animator, Hayao Miyazaki, just to name one giant who’s been disgraced by the recent prevalence of “AI slop.”

Hayao Miyazaki, an inspiration in the world of animation and cinema, has directed many popular and adored movies such as “My Neighbor Totoro” (1988), “Kiki’s Delivery Service” (1989), “Howl’s Moving Castle” (2010) and many more. With such lively and realistic but also impressionistic and iconic films, it was a surprise to no one that Miyazaki had a brutally truthful response to AI years before it became widely available to all.

In 2016, during a meeting to discuss AI and its abilities, animators using AI-programmed technology had the hope of showing Miyazaki another side of artistic evolution. In the since-widely circulated video clip of the auteur’s reaction to early AI, Miyazaki seemed like he had seen enough. After the showing, Miyazaki passionately speaks about a machine attempting to recreate an artist’s ingenuity, ending with what has since become a siren call for AI haters everywhere, “I am utterly disgusted…I strongly feel that this is an insult to life itself.”

After Miyazaki’s short speech, the animators stare back in silence, understandably. Miyazaki, coming from a different time and becoming renowned for a very human and old-fashioned style of animation, showed his distaste. But like anything else, art can rapidly evolve, and in some ways, become something more than human. The unknown, however, is still naturally something that most if not all humans fear. In early March, this exact fear showed up on the White House’s account on social media platform X, formerly known as Twitter, taking the internet by storm. The AI-generated image shows a drug dealer in handcuffs being taken away by a county sheriff, both eerily resembling Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli-style animation. Although images like these are simply meant to poke fun and toe a creative line, they are also admittedly doorways for inappropriate, even bigoted messaging.

Skepticism of AI in the arts and society at large also remains largely connected to the idea of robots and programmed systems one day potentially “taking over” certain aspects of our world, which is arguably as rooted in science fiction as it is in reality.

“I would want robots to assist humans,” Darryl Suwisanto (11) said. “Instead of taking their jobs, they should be assistants and help make their job easier. I would want robots [AI] to assist humans.”

Rather than being consumed by technology or completely rejecting it, can we evolve, embrace and incorporate innovation? The future doesn’t have to be a takeover. It can be a collaboration.