On the 2022 National Report Card, nearly 70% of eighth graders scored “below proficient.” The remaining 30% scored below average. In a typical classroom, about 25 children, 17 of them would be struggling to comprehend basic textual fiction and nonfiction. With 2024’s test scores predicted to continue this downward trend, it’s becoming clear that kids today can’t read, and it’s becoming a problem.

The public literacy system in the U.S. has a structure. Diagnostic testing, explicit instruction, and cumulative assessment may seem logical to the naked eye. The average student-teacher interaction is whole-group, but one-on-one instruction is a core element too, helping students comprehend all those words better in an individualized setting. What’s up with all this needless critique then? Isn’t it pretty obvious that our country’s literacy system has a clear rhyme and reason to it? Isn’t this the way things should be?

These many assumptions, however, fall under falsified conjecture. There are flaws within the system’s whole central philosophy, and there’s plenty of room to acknowledge this and do better. Clearly the curriculum and teaching methods currently being used have been largely outdated for a long while, as they don’t serve to help students. We should throw out the system of guesswork and estimating we’ve been employing recently within the last 20 years and instead help children hone their reading skills by having them sound out the words firstly and then connect ideas from there in a finely tuned logical manner. That’s a much better solution in comparison to simply telling them to “think of a word that makes sense” or “look at the picture.” Students need to learn how to utilize the many letters of the alphabet more actively, both the phonics and the syllables. How else could they possibly learn to read correctly?

“I believe that the majority [of students] have a stable foundation, but when students choose to pick up their phones instead of books. they are taking steps back instead of forward,” Columbia Heights High School (CHHS) English teacher Ms. Michelle Douglas said. “Just like choosing to practice an instrument or not, [reading requires practice too].”

Alas, this rhetoric isn’t considered common knowledge. Now, in addition to children’s capricious wills to learn, both unclear and abstract reading curriculums are now often implemented in classrooms. To rub more salt in the wound, this system neglects children when it comes to assisting them in sounding out and properly pronouncing words, hindering their ability to develop effective reading skills later down the line. With this information at hand, it is with obvious sarcasm that one wonders how reading scores have gone down in recent years.

“For decades, schools have taught children the strategies of struggling readers, using a theory that cognitive scientists have repeatedly debunked,” Emily Hanford of American Public Media reported in conjunction with the podcast “Sold a Story”, which was a surprise hit last year among parents and literacy advocates. “[Experts for so long have] argued that as people read, they make predictions about the words on the page using these three cues: graphic, syntactic and semantic.”

Many parents and teachers still today don’t realize that there’s anything inherently wrong with this kind of cue-based strategy and corresponding curriculum, and that it actually develops less proficient readers. Graphic cues, or guessing based on images on a page, are particularly harmful in actual phonetic language learning. Syntactic and semantic cues are also heavily rooted in estimating, considering possible functions or contexts of the word in order to figure out—once again, mostly ignoring the actual combinations of letter sounds and syllables in front of the student on the page.

To further elaborate, there is a prevalent issue with how the system handles readying teachers to teach reading in the first place. Ironically, colleges and universities have for years now failed to instruct our educators on teaching effective reading skills to their students. This is very unfortunate for those learning how to read because sufficient or high reading skills can make way for more imagination, opening up young minds and helping them discover and retain new knowledge. When teachers don’t have that skill to open up those pathways, we students become lost in the process.

“We always try to do better, and we always are trying to make things work for kids who struggle with reading,” Valley View Elementary EL teacher Mr. Mark Renner said. “We tried some things, and now we see they didn’t work. So teaching literacy is just harder than we thought it would be.”

With school instructors scratching their heads, our local government has decided to take things into its own hands. On July 1, 2023, the READ Act, officially named the Minnesota Reading to Ensure Academic Development Act, took effect and superseded the Read Well by Third Grade (RWBTG) initiative. Instead of focusing solely on kids magically knowing how to read by the 3rd grade, the READ Act ensures that all children in Minnesota read above or at their grade level every year. This is a significant change. In Minnesota, this new law is actively investing more effort into the education of children. There are additional resources being put in place as of right now, even. Take the fact that schools and districts now receive Literacy Aid funding for paying teachers for training and purchasing books and curriculum for the classroom. This potentially could help teachers, parents, and guardians in helping children become more successful readers and raising those test scores. However, zooming out and looking at things on a grander scale, this act and similar only seems to apply to 40 out of 50 states. Although when you look into things, there isn’t a discernible trend to be found. What exactly is stopping the 10 remaining states from signing the act is a cause for wonder.

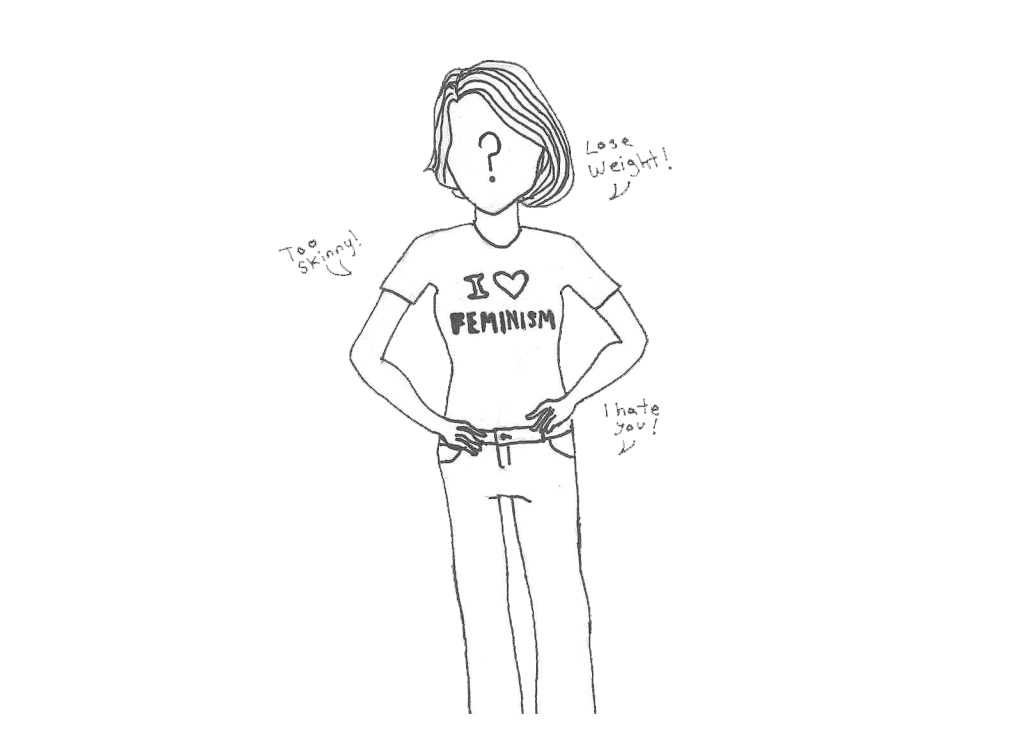

Poor literacy skills have devastating consequences beyond the classroom too. They can lower self-esteem, increase behavioral problems, diminish employment opportunities and even result in youth turning to criminal activities. According to Early Literacy Foundation, 85% of all juveniles who interface with the juvenile court system are functionally low literate.

This is not a mild issue, and action should definitely be taken to reduce these more than bleak possibilities for young minds moving forward.

With great concern, it can be noted that developing reading skills have historically not remained a primary focus once students have passed the third grade. It’s clearly shoved aside, even neglected. The Columbia Academy (CA) library was closed for a year before parent volunteers worked to bring it back to life, and the CHHS library is still largely full of books that are 10+ years old. Believe it or not, a commonality that both St. Paul and CHHS share is a lack of Media Specialists, more commonly known as librarians. Both districts (among others nationwide) have cut the licensed position due to budget limitations caused by inflation and decreased tax revenue. Hoping against hope, renovations still have the slim potential to be made to help these poor students navigate both basic and complicated text in their day-to-day lives. But the greater the age, the greater the distractions, the bigger the problem. Ultimately, though, doesn’t it come down to ourselves?