With months of discussion, a bill that claims to provide a plan to protect children online has garnered over 60 backers in the U.S. senate. Initially proposed in 2022, it serves to impose extensive new requirements on digital platforms, all to ensure that children aren’t harmed by their products. This bill, referred to as the Kids Online Safety Act (KOSA), operates under the pretense that elements of social media sites and elsewhere online could worsen depression, bullying, harassment and other issues. Recently, the act has tested the waters of controversy. Startlingly similar to a Trojan horse that could harm more than it purports to help, hints of it being potentially enforced raise considerable concern. The bill is relatively recent in its introduction, though widely popular especially among center-right and conservative legislators, and discussed as if it were predicting the internet catching fire without taking proper action. Its terms outline that they aim to protect kids’ safety online through government intervention, which should be a good thing, right? After all, children ought to be protected in this corrupt society in which we live.

At least that seems to be the first argument around the bill, though its language thus far seems to fall short in several respects. Parents across the nation and even some kids have voiced support for governmental restrictions, but the lack of substance and enforceable protocols calls into question its usefulness as actual protection online.

At the end of the day, even if mass government surveillance were logistical, the question is really if the government should do a parent’s job of monitoring their kids’ online activity. If you leave a young kid alone on an iPad with full access to the internet, we should know who’s to blame.

Furthermore, parents often neglect to enforce limits (not to mention unfettered access) on their offspring, which is another obvious issue this proposed bill obfuscates. We’ve all seen that one kid screaming his head off at a restaurant, only to be silenced by an iPad — this is the problem, not access once online but rather parental permission and encouragement to succumb oneself to the online world. Of course, parenting is no easy feat, and day-to-day life is easier when you can simply place an electronic device in front of your child. It can be a makeshift babysitter, allowing caretakers to take care of more important responsibilities, serving as a “temporary fix.” But these short-term solutions can add up to long-term consequences. Perhaps this is where the government should get creative and restrictive rather than assuming the worst of all minors’ online exploration.

Screen addiction inherently makes children more prone to social recluse, since spending so much time on a device lessens the time they spend interacting with others. Time used too much on devices can also lead to poor anger management issues, as sensory overload — an extreme overload of all the five senses but in lesser capacity — can trigger children into more negative moods and behaviors, as multiple studies have shown, including the now infamous Dunn Sensory Profile.

Overt device use has also proven to shorten attention spans, as many social media apps that kids routinely frequent feature all sorts of distractions and eye-catching things that make the real world pale in comparison, and not to mention that it impacts academic performance. Many teachers are adapting to a shorter lesson plan in order to accommodate to students with short attention spans, as one source mentions. But some teachers simply view it as a hurdle in their everyday jobs.

“When I taught high school, it was more of a disruption that I had to work with,” Highland Elementary LEAP teacher Ms. Kathleen Kerber said.

There are also the more concerning aspects of allowing children full access to the worldwide web without proper parent controls and guidance, such as viewing inappropriate content not suited for them. When socially isolated and online, minors even chat with people they otherwise wouldn’t trust in real life, under the guise that they’re a friend the same age as them when, in reality, it could be a full-grown adult. Such concerns have understandably worried many families, including older siblings that see the dangers posed to their younger brothers and sisters.

“Sometimes, I worry that she’s getting bad ideas from the content [my little sister] watches.” Kendra Deitering (10) said.

These might suggest good reasons for the KOSA being put in place. But at the end of the day, the issue stems from the parenting and “guidance” the children are receiving — not children’s ability to easily access all corners of the worldwide web. Sure, it can be difficult to navigate the digital age, but how many excuses can you make until you’ve simply ran out? Guardians need to take a step forward and assume their roles instead of the government doing it for them.

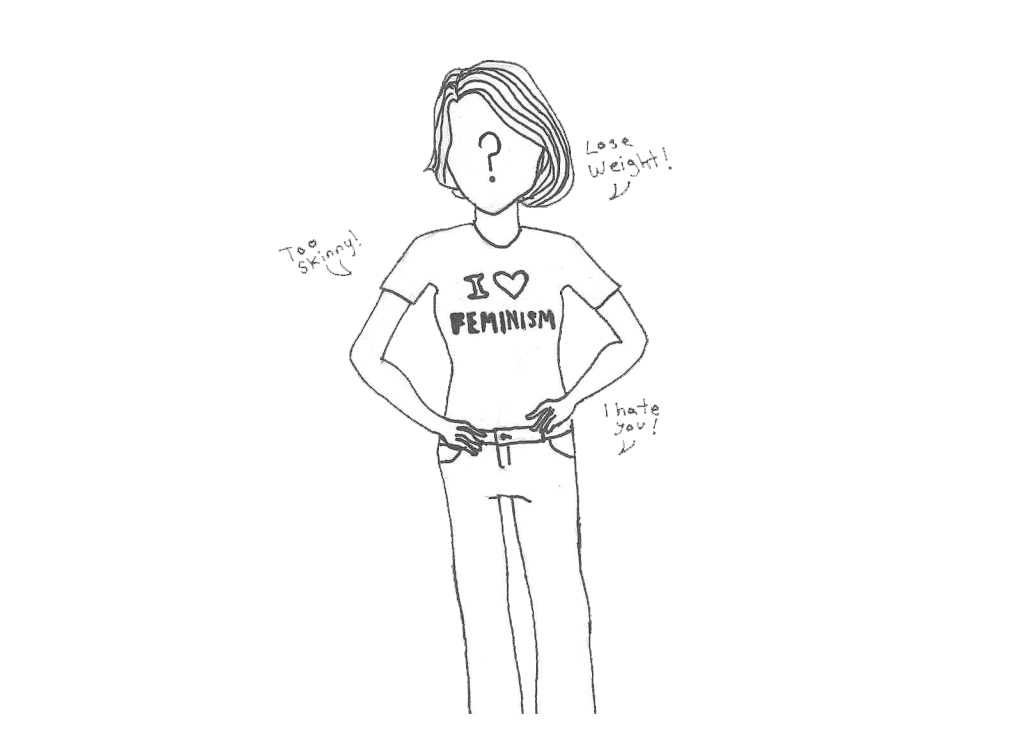

This bill also threatens anonymity, killing a lot of public spaces because kids frequent them so often under users and handles. Nobody would want their name tied to their online activity — it’s quite frankly, counterproductive and appalling to anyone who considers themselves an advocate of free speech.

There’s a good chance that the people who proposed this want to appear good in the public eye. There’s also the question as to how this would be a purview of law enforcement. How can a bunch of politicians and state and city workers rewire the entire internet as we know it? That’d take a substantial amount of both time and effort, not to mention countless lawsuits with very wealthy corporations that proliferate online.

The KOSA carries many flaws, and the theory of the enforcement in practice is just — simply put — illogical and insubstantial, though this is what we can expect from a biased but vocal minority.