Doesn’t it seem like every single year, higher grades are given out for the same level of effort? As though students are both getting better grades and getting more complacent at the same time? This is what is known today as grade inflation.

Grade inflation—similar to inflation in the economy—is when higher letter grades and scores are awarded to students for lower quality or effort than in previous years. Many teachers and parents are quick to identify and point out grade inflation, often wondering why educators are being so lenient with grade distribution, while others push back on the theory citing a lack of hard evidence. Defined most commonly as when As and Bs are given out when that same work may have been given a C just a few years ago, there are plenty of clues that suggest this is happening right here at Columbia Heights High School (CHHS), if not necessarily nationwide.

For the most part, including here at Heights, grade inflation unintentionally happens and should not necessarily be seen in a negative light, because educational best practices are always changing. Teachers are more likely to give accommodations to students who need them, such as extending deadlines for extenuating circumstances, as well as moving towards grading based on completion or accomplishment, not perfection.

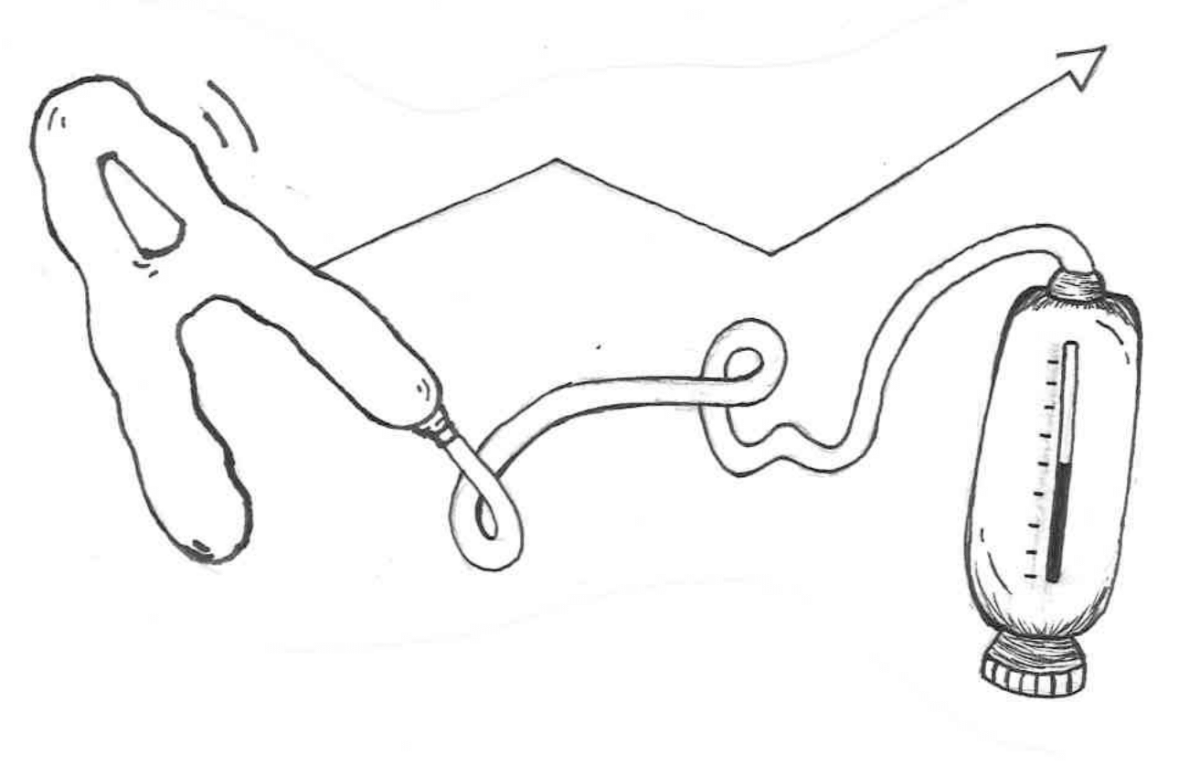

Many test scores like the ACT and SAT help to prove the presence and issue of grade inflation, showing that as students’ GPAs continue to increase, test scores don’t exactly match up. When students’ grades contradict test scores, it shows that one of the two is flawed, since tests tend to be direct representations of students’ proficiency in subject matters. National ACT scores are at a 30-year all-time low, averaging a score of 19.5 out of 36 in 2023, similar to SAT scores which have been steadily declining and are also at a national all-time low. From 2018 to 2023, the average SAT score has dropped from 1068 to 1028, out of 1600. GPAs on the other hand have been on the rise, jumping from an average of 3.17 in 2010 to 3.36 in 2021.

Although grade inflation doesn’t necessarily happen in any one specific or intentional fashion, it can be seen to occur in two main ways: lowering expectations by assigning easier tasks and/or being more lenient/accommodating towards students.

“[Symptoms of grade inflation] could include extended deadlines, lack of standards-based grading, accommodations for extenuating circumstances and health issues (COVID),” CHHS English teacher Ms. Tina Schaefer said.

So why does grade inflation exist? Is it because students are just getting worse? The declining test scores point to the belief that in these subsequent years, students just aren’t learning as much as they used to. Educators and education experts are concluding that kids are getting worse and worse in their critical thinking skills and that reading and writing levels are declining.

One major factor in the occurrence of grade inflation that is not mentioned enough is the huge effect of the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 has not only affected the balance between rising GPAs and test scores, but it has also caused a rise in behavioral issues, student engagement, attendance and more. According to McKinsley and Company, a management consulting firm based in Minneapolis, the pandemic has left students as many as five months behind in both mathematics and reading skills. Grade inflation tends to happen over long stretches of time, but in the years during and after the pandemic, it has been taking place at an alarming rate.

“I do observe, on a weekly basis, students cheating, and that could lead to students getting better grades than what their actual proficiency is,” CHHS Social Studies teacher Ms. Natasha Olubajo said.

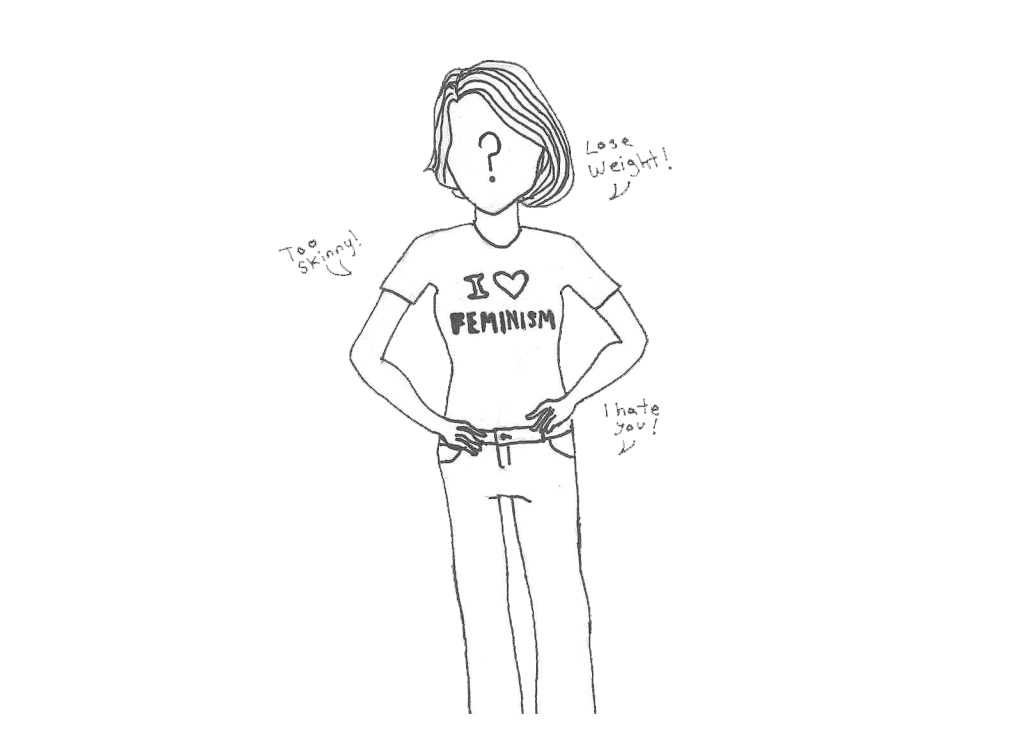

Another viewpoint to consider is that students should not be the center of blame for this issue because they’re struggling more in this modern day than ever before with growing pressure from parents, society, teachers and so many other sources. Add to this the fact that so much of the public education system punishes (suspensions, zero tolerance policies, expulsions) rather than uplifts (mental health, English learner support, individualized learning plans). Meanwhile, the talking points that remain most popular, particularly among educators and parents, are that students are getting dumber and lazier, and teachers are becoming too lenient with distributing grades, despite the majority of the research not supporting either of these claims.

So…what’s the solution? Should we let the lower-performing students fail and call it tough love or offer more support to those who are struggling, therefore potentially contributing further to grade inflation? Grade inflation is a phenomenon that is not meant to blame individuals — rather, it should serve as a means to assess the evolution of metrics for success. After all, true success in life is in the eye of the beholder.