“Question Number 14: What is the name of the woman whose cervical cancer tumor cells-”

Buzz!

“Team B?”

“Henrietta Lacks.”

“Correct!”

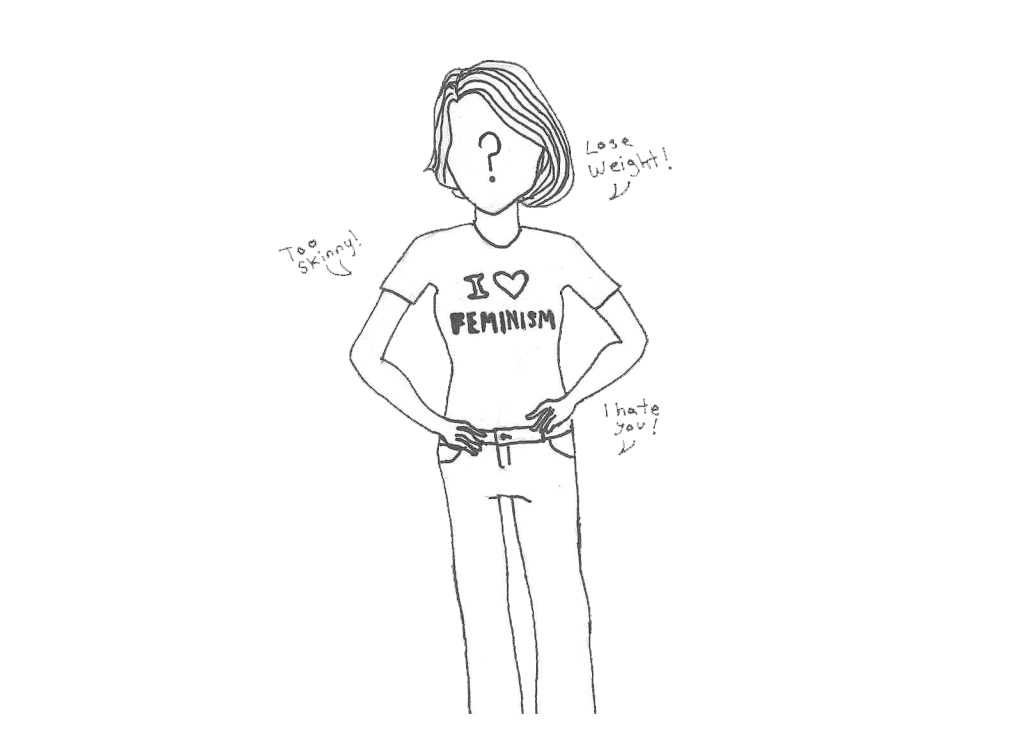

Science and Knowledge Bowl (to name just a couple) are the outlying “brains” of the predominantly “brawn”-centered world of school-sponsored competitions, but they share one insidious similarity — the chances of winning are more reliant on the students’ finances than any true skill or merit. The array of intelligence or performance-based competitions in schools is inherently flawed.

The Minnesota State High School League facilitates a number of non-athletic competitions, such as the one-act play, robotics, speech and debate. Additionally, there is Science Bowl, Math Team, Envirothon and Knowledge Bowl that are privately funded and/or regulated by specialty organizations.

The commonality between the leading teams of these activities is the high average income in the corresponding district boundary, or being private schools. There are several reasons that the income level of students’ families affects their performance in supposed merit-based competitions. The most blatant reason is that schools in affluent areas receive higher levels of funding due to the population owning high-value property, thus allowing public schools more funding despite similar levels of taxation.

Wealthy school districts are thus able to allocate more spending toward activities that are not as popular as athletic competitions, when districts with lower average income struggle to offer many basic educational needs, let alone well-funded extracurriculars. The distribution of funds is especially prevalent in activities that require schools to purchase or otherwise provide materials needed to be a competitor; this is seen in activities such as robotics — which requires motors, platforms for programming, controllers, and various other building supplies — and the one-act play, which requires the purchase of scripts, as well as purchase or creation of set-pieces and costuming. The required resources create a significant paywall for schools to participate and for students to access opportunities to put their skills to the test.

High-income schools are more likely to grant a range of opportunities for advanced courses such as Advanced Placement (AP) Computer Science and Calculus, or International Baccalaureate (IB) courses. These require instructors with highly specialized skill sets and educational backgrounds that the majority of teachers, especially younger ones, don’t typically have. These opportunities provide high-income or students attending private schools a significant advantage over low-income students in trivia- or logic-based competitions. No matter how hard low-income students toil in order to become more knowledgeable on highly specific topics, they are at a significant disadvantage.

“Schools with higher incomes have more programs available from a young age for their students, which puts them at an early advantage over the limited learning opportunities that are possible at lower-income schools,” Columbia Heights High School (CHHS) Knowledge and Science Bowl member Alazar Getachew (12) said.

Another factor that is blatant in the inequity of school-proctored competitions is the privileged home lives of the students involved. Students raised in families that are college-educated and fluent in the English language often perform higher in standardized testing like the SATs, ACTs and MCAs than students who do not have these privileges (each factor correlates, on average, with students’ families’ economic status), concepts covered by standardized testing have a high likelihood to be covered in knowledge-based competitions — not to mention the fact that students with wealthy parents are more likely to partake in private tutoring.

Less blatant reasons that low-income students are at a disadvantage at non-athletic school competitions is how many of them have to work after school and during weekends to save for higher education or support themselves or their families, as having a job may conflict with the times of practice and/or tournament dates.

With the odds stacked against low-income students, is there a proper solution to addressing this inequity? Socio-economic status affects school athletics too, but most sports require separate divisions based on skill level and enjoy revenue from ticket sales, among other benefits that make funding easier, especially for popular sports such as basketball and football. While this could be crucial in order to ensure equity in non-sporting competitions, the small number of schools that are involved in these competitions may pose an issue of finding fair competition.