The people of Sudan have experienced genocide and civil war for decades.

Before Sudan became independent in 1956, favoritism affected Sudan’s diverse ethnic communities because of British-Egyptian governmental control. This unequal treatment of indigenous Sudanese people created regional and interreligious hostility, which led to numerous future conflicts even after the country gained independence. The midcentury central government was heavily influenced by Arab elitists who used their power to access land and other Sudanese resources. This often disadvantaged non-Arabs like those in the Western and Southern regions Darfur, South Kordofan and Blue Nile. The increased discontent between these regions’ peoples and the Arab communities set the stage for ethnic cleansing, targeting specific ethnic groups in Sudan, leading to the tragic events taking place today.

In the late 20th century, tensions and violence between Arab-dominated government forces and non-Arab groups in Darfur rose over land and natural resources. Then, in the early 2000s, the conflict escalated, which led to displacement and widespread suffering of specific groups in Darfur like the Fur, Masalit, Zaghawa and others. Fast forward to November of last year, when a new genocide began, causing the nation’s population to once again decline at an unsteady rate.

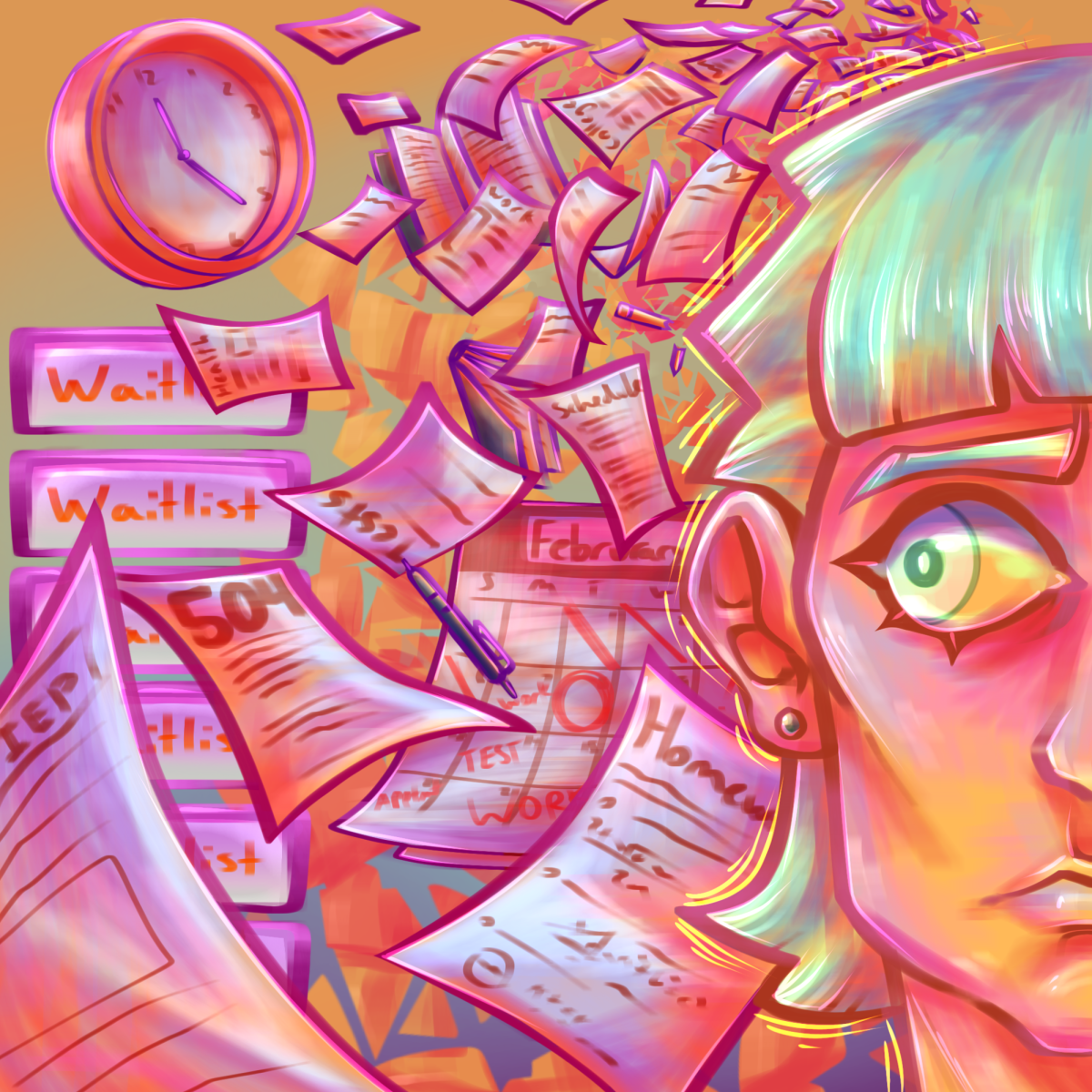

“There’s a few major world conflicts going on all over the world right now and social media brings awareness to some more than others. With Darfur, there has been news about the ongoing war in the past, but if it had more attention now, people would be getting involved from many different places,” Columbia Heights High School Social Studies teacher Ms. Edwardson Stern said. “I would see articles about what is happening in Sudan and would want to know more but there wouldn’t be enough information. Also seeing genocides all happening at the same time desensitizes people because they feel helpless.”

There are also ongoing conflicts in Eastern Sudan involving the Beja, Beni Amer and Nuba people, who in addition to struggles of land ownership and resource hoarding, face unfair representation and agricultural challenges. The South Kordofan and Blue Nile conflict that lasted from 2011 until 2020 had similar ripple effects that continue to this day. The Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N) was more recently borne out of these lasting clashes just as the Sudan Liberation Movement (SPLM) in the South was in 2002. Both are rebel armies organized to combat oppressive governmental forces.

The latter sprung up due to the Darfur region’s humanitarian crisis, which received significant media attention because of how severe the conflict was and the fact that it did not subside for years. In places affected by conflicts such as these, women became more at risk for sexual assault (as did men) because the social systems that break down cause chaos. Because of the collapse of social structures, civilians felt less secure in tough situations when they had no shelter while being displaced. The lack of protection makes women and other unarmed individuals in these areas more vulnerable, making life harder for these communities, much of which is rearing its head again today.

The crisis in Darfur led to the focus on humanitarian efforts to address the cruelty occurring in the region. The other groups in the different regions do not have the same level of media coverage as Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa groups but are equally crucial issues that contribute to the unstable crises within Sudan. As the rest of the world tries to grasp the frightening reality of war in Darfur, specifically because the levels of violence have increased over the decades, it’s something the Sudanese people deal with daily and do not know if it’s ever going to completely end.

Since April 2023, more than half a million deaths have happened according to the United Nations (UN). The RSF, or Rapid Support Forces (formerly known as Janjaweed militia), and their commander Hemidti stated that Arab countries such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE) are “investing” in Sudan’s government to win the war, even if it means taking children and conscripting them into soldiers for war. Even some non-Arab countries like Russia, with the help of its state-funded private military, the Wagner Group, have helped fund the ongoing attempts at gaining control of Sudanese land to exploit the fledgling nation’s natural resources like gold.

This group in particular has been accused of propping up Sudanese dictator Omar al-Bishar, who currently has no opponents in the race for the presidency despite the countless societal unrest.

UN Special Advisor Alice Wairimu Nderitu warns people about the RSE and Sudanese military and other groups involved that attacked the ethnic communities that could lead to more war crimes.

Millions of people all over Sudan need humanitarian aid. Groups include the Beja and Beni Amer in the East, the Nuba people in the South and many more struggle to.

“It’s heartbreaking that Sudan is in the middle of a war and the mainstream media is not showing as much as they need to and if they were to bring awareness to the ethnic cleansing,” Nadifa Bashir (11) said. “People might not understand the severity of the situation. So I think we need to voice this conflict in a better way.”

It is the people who come from stable and privileged backgrounds that become government officials, and other than the protests within some small areas in the country, no enforcement of human rights from the rest of the world is happening. In the meantime, Sudanese civilians can only do so much to stay away from the battlefields between these relentless military groups.