Muslim women across all nations have been facing discrimination for centuries, and France has been no different, regardless of any attempt to suggest otherwise. After the 2010 ban on the niqab (a face covering worn by some Muslim women), another female Islamic clothing dispute in France has stirred countless discussions about religious freedom and cultural identity, with some claiming that prohibition violates religious freedom, infringing once again on a key sign of Muslim women’s identity.

The abaya is a head-to-toe garment worn by Islamic women, with a far less targeted equivalent for men known as the qamis. Modesty is an important part of Islamic culture, and nearly all Muslims are taught from childhood to hide themselves from non-mahrams (those with whom marriage is prohibited due to a blood connection). With the exception of revealing their hands and faces, Muslim women cover themselves from head to toe as a customary religious practice. In addition, men are not permitted to reveal anything above their knees.

The restriction, which for now is limited to public middle and high schools in the European country, demonstrates how French officials and governmental agencies collaborate to maintain institutional racism, xenophobia and Islamophobia, tying into a history of subjugating the bodies of Muslim women. The latest Abaya ban in France has once more reignited a heated debate about whether it is ethical or unethical to restrict public displays of faith, creating serious questions about religious freedom.

“The abaya signifies who I am to me; it denotes modesty and elegance,” Nadifa Hussien (11) said. “We have religious freedom in America, and I am proud to wear my abaya. I feel like [a ban] would take [away] my independence to express myself through my dress choices.”.

In 2004, France prohibited all religious symbols in schools, including hijabs — headscarves many Muslim women wear. They had also banned large Christian crosses and Jewish kippahs. Since then, France has proceeded to forcefully legislate the bodies of Muslim women, dictating what they can and cannot wear, with restrictions on burqas, in addition to niqabs, in the streets. Islamophobic laws have plagued Muslims living in France over and over again, from the 2020 policy known as Systematic Obstruction, which authoritatively sanctioned fear-mongering under the guise of “anti-radicalism,” and 2021’s Anti-Separatism law, which disallowed public sector employees from voicing or displaying religious beliefs.

In 2023, the administration of French President Emmanuel Macron defended the abaya ban by claiming the fundamental concept of equality and secularism necessitated a restriction on overtly religious clothing of all varieties. However, it is difficult to see how a relative handful of Islamic children dressed in abayas constitute a threat to France’s humanism, let alone how a ban on religious freedom and expression can be construed as evidence of striving for “equality.”

“This implicitly legitimizes discrimination based on race and religion,” human rights lawyer Nabil Boudi said on French television news network BFM. “If my name is Samira and I am wearing a kimono or abaya, it is religious clothing; but if my name is Sophie and I wear the same kimono, then it’s not religious clothing.”

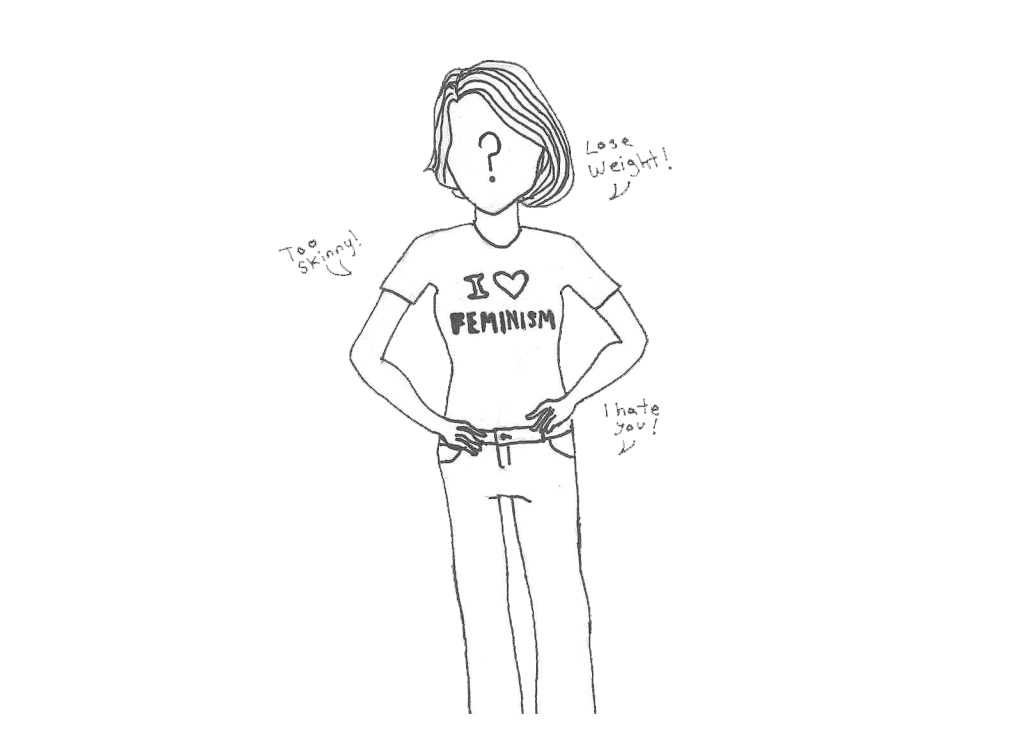

In the United States, there is constitutionally protected freedom of religious practice in and out of school (via the First Amendment), but even though one is not prohibited from wearing the abaya, wearing it is difficult enough according to Westernized beauty standards. Even when addressing this morass of sexist history and expectations, there is often another point of contention Muslim women face in America known as Western feminism. A lack of intersectional perspective causes Western feminists to view components of Islamic values such as head coverings as examples of “oppression.” Western feminists who sit outside of intersectional feminism should recognize that Muslim women can define feminism for themselves. Muslims are free political agents who can choose their own terms of liberation rather than being forcibly released from an outsider’s perceived cage.

This only leads to rebellion and outspokenness, which are both supposed values of most feminists. For instance, when France banned the abaya in the secondary grades, it caused more than 300 girls to defy it; most agreed with changing, yes, but others got sent home and had their chance at an education taken away from them unless they adhered to an oppressive rule.

This barbaric practice is ironically seen by its proponents as a “civilizing mission,” assuming that Muslim women do not know how to be free and must be saved from their own “backward” culture and religion. How can one claim to be standing for equality by an action, while that action is actively discriminating against a whole group of people? France’s stance on religious freedom targets many Islamic practices and violates the inherent right to self-expression.