Many would think that the number one cause of death today for American youth is cancer, car accidents or suicide, but according to numerous sources such as U.S. News & World Report and the National Institute of Health, it is guns. Gun violence, and specifically gun violence in schools, is killing American youth at a higher rate than any other cause of death.

As of October 26, there have been a total of 565 mass shootings in America, 58 of which have been school shootings. According to Fox 9, there have been about 103 cases of gun violence in Minnesota schools alone as of October. This year in Minnesota there have been countless threats and lockdowns due to possible violence too, such as a 17-year-old arrested for threats made against Edina High School in September, a lockdown at a school in New Hope after a recovered firearm outside of the school and two threats to Maple Grove Middle School in the same week. Most recently, guns were found in multiple high schoolers’ backpacks following a physical altercation at Robbinsdale-Cooper High School.

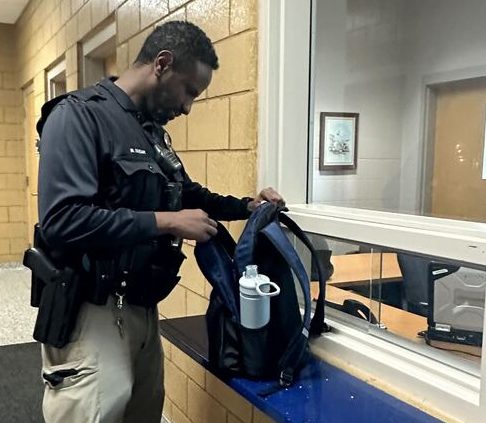

Nearly every school in the country is searching for solutions to the constant threat of gun violence. One solution being explored is the use of clear backpacks and/or the prohibition of backpacks in general in order to prevent firearms from entering school premises. Some schools, such as those in Broward County, Florida, require all backpacks, bags, lunchboxes and duffel bags in the school to be clear. South River Public Schools in New Jersey also require clear backpacks and bags for all students in the district, from elementary grades all the way to high school. But these instances don’t stop there; Flint Community Schools in Michigan banned backpacks entirely for grade levels 7-12.

While this seems like a direct way to solve the issue of guns being illegally brought into schools for the intention of harm, those who oppose these policies comment on how it’s ironic that the U.S. would rather regulate backpacks than guns.

“I feel as though [banning backpacks] would be a violation of privacy,” Taymoi Epps (11) said. “While I understand the reasoning for it, an overall expunging of a backpack would make everything more inconvenient.”

Adding on to the issues concerning school safety is the recent removal of school resource officers (SROs) in various metro area districts, including Columbia Heights Public Schools (CHPS). A Minnesota law was passed earlier this year that prohibits officers from “placing a student in a face-down position” along with other specific holds when restraining students. As a response to this recent law, many Minnesota police departments have withdrawn SROs because of the possible interpretation that the law could put SROs more at risk for criminal charges than before, as well as limiting their ability to do their jobs. There are many differing opinions about whether or not SROs belong in schools, and questions have arisen of the safety that they really bring to schools, especially in light of police violence such as the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis officers. Some students themselves say the presence of law enforcement in school makes them feel unsafe, while others believe that school resource officers should be in schools to help prevent and intervene in situations of conflict.

“Our school district, staff and students have built very strong relationships with our SROs,” Principal Todd Wynne said. “We had a lot of kids who would get advice and/or support from the officers with things that happened outside of school.”

In addition, without the presence of police or other campus/hallway monitors, Columbia Heights High School (CHHS) students and faculty ponder whether the use of side doors during school hours has become a question of safety. At all times, students are prohibited from exiting, entering or opening any entrance other than the front doors. With five different back and side doors, there’s no way to surveil every one of them at all times, causing difficulties in making sure no students are being let in and out by peers during the school day. One incident that happened in CHHS late September was a situation where three students from another school were let into the building through a side door entrance, and in response, CHHS was put on hold, keeping students in classrooms while administrators checked hallways for said trespassers.

“I would say I feel safe around Heights,” Leo Pham (11) said. “It never seems like any fights are going to happen and if they do I feel like it would be pretty contained and dealt with quickly.”

A common practice to prepare students for the possibilities of threatening situations is lockdown drills. Minnesota schools have a state mandated requirement of five lockdown drills per school year, not to be confused with active shooter lockdown drills, which specifically simulate and prepare for armed intruders and are not required to be performed in any Minnesota schools. Some say that lockdown drills, especially active shooter drills, are unnecessarily anxiety- and stress-inducing for students and staff. Common rebuttals state that these drills, similar to fire drills, aptly prepare students for the tragic possibility of a dangerous situation, such as a school shooter. If students can become even a little bit more acclimated to these situations, they may be able to respond quickly with less anxiety if a real shooter situation were to happen, proponents argue, because they’ve been prepared by these lockdown drills.

There’s no denying that the occurrences of gun violence are becoming increasingly prevalent, but what measures are really going to be efficient in combating and preventing these tragedies? On the one hand, banning backpacks and the repetition of lockdown drills may help to stop guns from entering schools and equip students and educators with the awareness and familiarity needed to deal with such a scenario, but do these safety measures truly have a net positive effect, or are they just another disruption or, worse, source of trauma?