Teacher shortages nationwide raise concerns among staff, students

Teaching is an art that has arguably gone underappreciated for great periods of time and in various ways. MetLife’s annual Survey of the American Teacher results for 2022 revealed that less than half of respondents feel that the public at large “respects them and views them as professionals,” a decrease from 77 percent of respondents 11 years prior.

This is a downward trend that has proliferated not just through a global pandemic, but also several nationally publicized school shootings, a Secretary of Education that believed public schools were “a dead end” and so much more.

The National Center for Education Statistics conducted a survey of districts around the country in October of last year that confirmed 45% of public schools had at least one teaching vacancy, with an overwhelming number of these positions in the fields of special education and English language learning.

There are so many reasons this is happening apart from general public perception and frightening mass tragedies, though. Morale is also down at least in part in the profession because, as shown by a PDK International poll of 1,000 American parents, a majority of adults “don’t trust teachers to handle sensitive issues like race or gender” in the classroom.

Perhaps even more disheartening to those in the profession is that the same poll reported only 37% of parents would want their own children to become teachers. For some educators, it’s frustrating to constantly hear these kinds of statistics, especially when they feel so passionate about what they do for a living.

“Not everybody can teach — not everybody has that innate ability,” says Mr. Daniel Honigs, a long-time math instructor at Columbia Heights High School (CHHS). “Teachers are constantly trying to figure out how to explain something differently in a way that accommodates every learning style, and there are loads out there!”

Another clear struggle facing educators and students alike, contributing to the ongoing shortage, is financial in nature. Districts that largely serve low-income students also largely underpay their workforce, including classroom teachers. Last March, the Sahan Journal reported that teacher salaries in Minneapolis Public Schools barely kept up with inflation, which is just one of the factors that led to a teacher’s strike in that district in the spring that lasted weeks..

Due to low funding, some schools also revert to cutting costs, and sometimes, eliminating positions — thereby increasing class sizes (unless enrollment drops too). Among the teachers of a given staff, the first to go are usually teachers at the start of their careers. This is dangerous because many BIPOC have begun entering the education workplace in higher numbers in recent years, and many believe BIPOC teachers should be in high demand in order to better represent the diversity of a school’s student body.

This teacher shortage trend has also started to hit Columbia Heights Public Schools (CHPS), with at least two positions opening up mid-year, leaving some students to face a stream of long- and short-term substitutes, as well as other teachers filling in when needed.

“[Students] frequently adjust to changes before they can begin to learn–[including] changes in the way a course is organized, the content it covers [and] the way it is taught,” Bruce Thomas, a senior enrolled in the Intro to Education course here at Columbia Heights High School (CHHS). “Our staff is willing to give up their free periods to help and support another classroom if needed.”

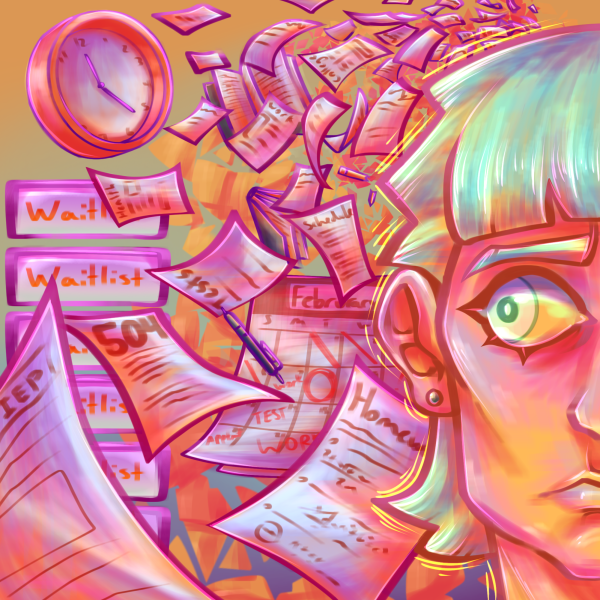

It is not only the teachers that are suffering from this shortage but also substitute teachers. The state of Minnesota’s biennial Teacher Supply and Demand Report from January found nine out of ten surveyed districts saying their access to substitute teacher pools has decreased significantly. This leaves staff taking on that role as well, which causes stress and inconvenience. The way it works is if a teacher is out and another has prep during the same hour, that teacher would then spend their prep subbing the absent teacher’s class.

Yet, prep time is extremely important and teachers use that time to make copies of worksheets, create their daily slides, etc., and it is built into teacher contracts nationwide, including here at CHPS. Losing that time is a grave inconvenience, although many teachers would take this on without a second thought in order for students to have a familiar face in their classroom. For lack of better words, class must go on.

And these classes are just getting bigger, adding to the concerns regarding teacher retention and staffing. Metro ECSU’s Annual Class Size Study for 2022 shows an increasing trend for class size statewide since 2016, with health and physical education classes, in particular, rising above a ratio of 30 students to one teacher in the secondary grades. This can be overwhelming for both teachers and students. Bigger classrooms can compromise student-to-teacher connection and understanding.

“If you have too many students in a classroom, teachers can’t often get to every single one of them,” Nick Goodman (12) said. “They should at least have someone in there helping them.”

With fewer teachers a part of the team, instructors find themselves carrying heavier loads when they already have one of the heaviest loads of all —educating the youth.

Naomi Gbor is a senior at CHHS. She values free-expression, nature and camaraderie. Her hope is to help keep journalism alive in a social-media-based society.