Anniversary of war on Indigenous people in Minnesota observed

Dozens of Indigenous people from two different tribes perished in the U.S.-Dakota War, which was observed on its 160th anniversary this past December.

I remember learning about the U.S.-Dakota war for about one week back in middle school. Although we did learn about the battle and how it ended, I do not recall going further in depth about why the war happened.

Now that I’m a senior in high school enrolled in American Indian Studies, I find myself learning more about what happened during the war, how it started and what the outcome of the war was. The number of people in Minnesota that have not learned about the aftermath or even the war itself is shocking. I believe It’s important to know how the war started.

“From what I remember it was never mentioned or even talked about in middle school,” Jesus Gonzalez (12) explained. “Students could benefit from learning about the event. During the war, many things occurred [that] could alter the perspective of how students view the U.S. government.”

Historical events, especially like this, can be uncomfortable to teach. One way we can help people learn about this, however, is through writing about it for a larger audience than just those enrolled in the aforementioned course taught by Ms. Sinicariello.

There were many reasons why this war broke out. Before the 1800s, the Dakota people were thriving on the land, growing food and trading with fur traders.

One of the main reasons fighting started was the breach of the white settlers’ treaties. Throughout 1805, when the settlers arrived in the Dakotas’ homeland, tribal and settler leaders signed treaties giving the land to colonizers in exchange for food and goods. From the start, these treaties were unfair, with the Dakotas not being able to read the writing—they were only trusting what the settlers told them. In addition to the use of military power, the settlers often threatened the Dakota with not being able to go home unless they sign the treaties. Once signed, however, the white settlers would end up taking more and more of the land without giving the Dakota the resources they needed, such as the food they were promised.

In 1805, explorer Zebulon Pike made a treaty with the Dakota people at Bdote, a very sacred site, to allow the U.S. government to build Fort St. Anthony (now Fort Snelling), which overlooks Bdote. Starting in the 1830s, the U.S. government started to cede land from the Dakota people left and right to allow settlers to live in Minnesota, culminating in the Treaty of Traverse de Sioux. In turn, the settlers forced the Dakota people to live on a strip of land just south of the Minnesota River in Southwest Minnesota. While the Dakota respected the treaty, the U.S. government failed to hold up their end of the deal.

The Dakota were starving, having been denied the very food and supplies they needed to survive. August 17, 1862 was when the war began. Four young Dakota men were looking for food, and they lucked out and found some chickens. This led to an argument with white settlers. Sources at the time were unsure who started it, but it ended up with the four Dakota men killing the five white settlers. This happened near Action Township, leading Taoyateduta (Little Crow) to reluctantly declare war on settlers. News of the uprising reached St. Paul on August 19, where governor Alexander Ramsey commissioned an army to fight the Dakota. The army was led by Henry Sibley, a fur trader and inexperienced general. Conflict continued for around a month until September 24 when Taoyateduta fled west and other warriors surrendered.

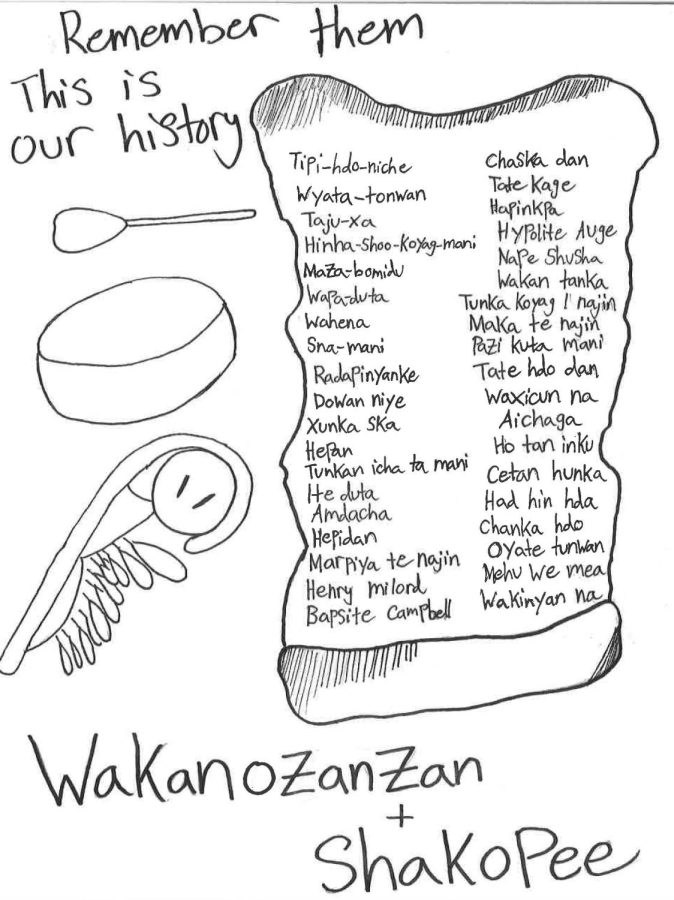

The aftermath of this war is nothing but tragic. The conflict only lasted 36 days, but the bloodshed on the battlefield was gruesome, resulting in the deaths of 400 white settlers and 50 to 100 Dakotans. This led to around 300 Dakota men being put on trial with looming death sentences. When Abraham Lincoln caught wind of this, that number was cut down to 38. So, on December 26, the biggest mass hanging in American history occurred. Elders, women and children were sent to concentration camps at Fort Snelling before all Dakota were banished from Minnesota by federal law in 1863. That law is still in effect today but is rarely enforced.

“For me, it’s not a choice [to teach it],” Columbia Heights High School (CHHS) social studies teacher Ms. Kristen Sinnicariello,, who has been teaching American Indian Studies for four years now, said. “I had a class at the University of Minnesota with a professor who inspired me to teach what we are learning now. I think it’s good to even just talk about the event with family members because some people who have lived in Minnesota all their lives don’t know that this event took place.”

Many Indigenous people now are suffering from horrible living conditions, have the highest rates for drug abuse and are still getting their land taken away by the government, such as the Line 3 pipeline.

Today, there have been efforts to reconcile with the white settlers about the war and more people know about this event. It is mandatory that all Minnesotans in sixth grade learn about the U.S.-Dakota War in their Social Studies class. A park near the hanging site in Mankato, Minnesota honors the Indigenous veterans of the war and those who paid a terrible price for fighting for their land.

One of the most famous ways to reconcile is the Dakota 38 + 2 ride, which embarked on its final trek this year. These riders started, as they have every year since 2005, at La Brule, South Dakota and ended at Reconciliation Park in Mankato 330 miles away, stopping to reconcile with non-Indigenous farmers and settlers on the way.

This war was nothing but tragic with a centuries-long aftermath continuing to hit hard for many Indigenous people. Fortunately, helping people learn about this is a great step toward supporting the Indigenous communities here in Minnesota and beyond.

Ymir Skokan is the manliest senior in the school and is Lead Podcaster for The Heights Herald. He is very free-flowing and likes talking about anything...