MN nurses fight against low pay, poor conditions

Twin Cities nurses gather to protest against unfair wages.

This story was originally published in the Heights Herald Print Edition.

Minnesota nurses have made history with strikes being held at 15 hospitals over the course of three days in September.

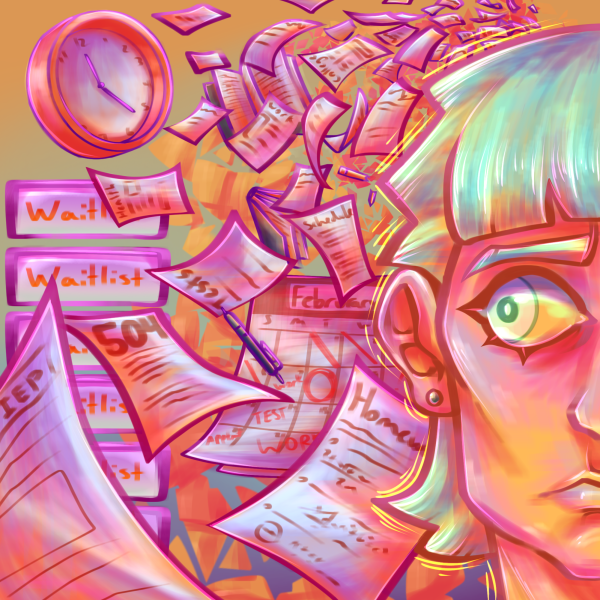

Working as a nurse comes with many challenges and tribulations. Along with the physical and emotional stress that comes with the job, many hospitals have been dealing with staff shortages as of late, requiring many nurses to be available to come in at any given time whether they have had proper time to rest or not, as a lot of nurses work sporadic shifts that can average eight to twelve hours. Considering all of this, many nurses have begun to advocate for better work conditions and salary increases.

The problems that led to the strikes in Minnesota during September weren’t far off from the national problems occurring in hospitals and clinics around the country. Though Minnesota does not have a shortage problem in regards to nurses, there is a problem with retention, as many nurses are quitting due to poor work conditions and patient care. The increasing number of nurses leaving hospitals results in patients having to wait longer instead of receiving care, including when it’s needed urgently.

“Enough is enough,” Minnesota Nurses Association (MNA) President Mary Turner said. “It is time to put patients before profits in our hospitals.” Said.

Nurses with the MNA had been in contract negotiations with hospital executives for six months before the strikes began. They asked to be included in discussions regarding staffing decisions and solutions to keep more nurses in hospitals. When their requests were not met, MNA members began to plan strikes to show that they were serious about these issues and would not settle for less. When put to a vote, the strikes were agreed upon overwhelmingly by nurses and began on September 12.

Of course, when over a dozen hospitals lost thousands of integral workers, they scrambled to fill those spots. Some positions were filled by physicians or non-nursing staff. In-state and out-of-state nurses were also brought into these hospitals on temporary contracts, many leaving right after the striking nurses returned to their hospitals.

Denise McDowell, a registered nurse with M Health Fairview Southdale Hospital (and, full disclosure, this writer’s mother), was one of the thousands who picketed outside of their hospitals September 12 through 15. She initially voted yes to striking to stand with her colleagues so that they could achieve goals essential to their jobs, including safe staffing, benefits and raises.

“[I felt] a little bit of nervousness because I have never been through a strike”, McDowell said. “[I was] proud to see all of the nurses and hear all the cars honking at us, supporting us.”

During the years that she has worked at Southdale, safety has come up as an issue multiple times. In September 2020, a failed carjacking attempt left a physician with a bullet injury in his scalp. The shooting occurred in the parking lot of the M Health Fairview Hospital. The hospital and nearby mall were both shut down as police investigated the assault while nurses and staff were warned to keep safe and stay out of the area. Safety issues in the daily lives of nurses, especially regarding violent patients constantly threatening their health, have risen over the years, as previously reported by both the Star Tribune and Minnesota Public Radio.

The ask for raises isn’t new either, with nurses asking for higher wages at the end of each of their contracts, usually lasting two years. During the years that she has worked at Southdale, McDowell can verify that the safety and staffing has deteriorated.

Though the strike didn’t personally affect her since she wasn’t scheduled to work on the striking days, McDowell empathizes with those that did lose three days of pay. Meanwhile, some nurses who crossed the picket line continued to work instead of going on strike with their peers.

Several nurses, both those that participated in the strike and those that did not, don’t feel like the strikes were very effective.

“[They’re] still in negotiations right now,” McDowell said. “I don’t think it accomplished what we wanted it to accomplish.”

Because the strikes were not as successful as MNA intended, nurses voted a second time on November 30, deciding whether they would like to strike again, this time for even longer. Members of the MNA stayed up for twenty-four hours in negotiations, resulting in a new contract that included a wage increase, improved safety measures and more. The strikes which saw thousands of nurses band together successfully reached the goals they set out to achieve at the beginning of the year.

Nurses are an essential part of the world of medicine and care. If they are not provided with the resources and environment they need, they can not work properly. These strikes are an accumulation of years of mistreatment of nurses that have finally decided that enough was enough. Only time will tell if the efforts of the MNA and all the nurses involved in these strikes will succeed in their goals, or if Minnesota hospitals will continue to lack thousands of essential workers.

Destiny McDowell is a senior at CHHS, and it’s her second year on The Heights Herald, this time as the Arts & Entertainment Editor. She enjoys eating...