Indigenous women spark needed movement

The No More Stolen Sisters movement, identifiable by the red handprint they often have covering their mouths, sheds important light on the high rate of missing and murdered Indigenous women.

Dating back to the colonialism of the 15th through the 18th century, Europeans killed and displaced Indigenous people from their lands and onto restrictive reservations. These reservations were generally unsuitable for agriculture, which still plays a huge role in the wealth, health and prosperity of Native Americans. Lack of opportunities, lack of property rights, and government and law enforcement abandonment lead to high rates of poverty and homelessness. And due to the isolated nature of these reservations, the mainstream media has largely, until recently, ignored the tragedies incurred by First Nations peoples nationwide.

The long overlooked crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women (so prevalent it is often abbreviated as MMIW) both here in the United States and to our north in Canada, which was also colonized by Europeans at roughly the same time, has finally come to the forefront. This includes right here in Minnesota.

“This year hundreds of pipeline workers came to Northern Minnesota to work on the Line 3 Pipeline that was being built throughout treaty lands,” Columbia Heights High School American Indian studies teacher Ms. Sinicariello said. “The influx of these ‘man camps’ of workers led to higher rates of sexual violence and assault against indigenous women as well. This is documented by many investigations and even court cases from this summer.”

Sadly, there are missing person statistics for other racial/ethnic groups, but the same can’t be said in most cases for native women. MMIW is a problem that all communities, especially allies, need to address.

“I think [it] is the symptom of many deeper issues in our society,” Sinicariello said. “Because of the trauma and genocide committed against Indigenous people, there is often high cases of drug and alcohol abuse on reservations. Continued oppression by the government and corporations also compounds the issue.”

For decades now, it has become clear that Indigenous women have been disproportionately kidnapped, violently murdered and sexually assaulted. The Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Task Force (MMIR) released data indicating Native people account for 1% of our population in Minnesota but make up 8% of murders in our state. According to a report sent to the legislature in December 2020, Indigenous women are also seven times more likely than white women to be murdered.

According to the Indian Urban Health Institute, federal agencies routinely neglect to correctly document the nationalities of victims found and don’t check whether the women are Indigenous or not, sometimes even classifying Indigenous women and girls as white.

With the already high death rate, and the lack of nation-wide support for locating these women/girls, no one can pinpoint the exact amount of Indigenous women murdered over any given span of time.

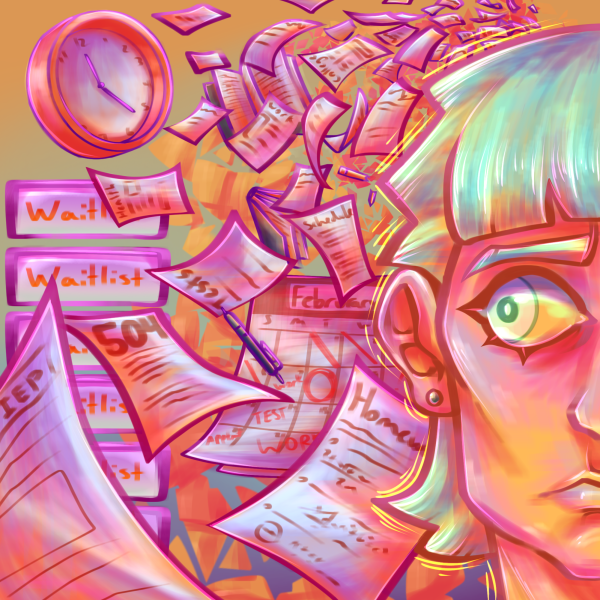

This sparked a movement known as “No More Stolen Sisters.” Earlier this year, powerful Native women leaders came together to protest the rate of missing and murdered Indigenous women, as well as how they are taking action and establishing movements, along with non-Native allies.

To mourn the spirits of stolen sisters, supporters of this mission use red paint to create a handprint that is plastered across the lower part of one’s face. This symbol is used all over North America because red is said to be the only color spirits see.

“The No More Stolen Sisters movement is definitely bringing much-needed awareness to this issue,” Sinicariello said. “I have seen many activists with red handprints covering their mouths at protests and red dresses left hanging up in order to draw attention to the women who are no longer with us today. I think these visuals demonstrate the inequities that are present in our communities but that remain unseen by many.”

As more and more position themselves to become allies of the No More Stolen Sisters Movement, these questions become more amplified than ever before. Why are the homicides of Indigenous women not considered high priority cases? Why is there always a national uproar for white women but not women of color?

The phenomenon known as missing white woman syndrome has become more resonant now than ever with the amount of media attention on recent cases like Gabby Petito. Well- known Journalist Naomi Ishisaki uncovered that Gabby Petito, the story of the missing white women gained over 340 million google searches. While Mary Johnson who is a native woman from the Tulalip tribe has been missing for over 10 months, and only had 6,000 google searches.

The Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Department of the Interior (DOI) have both taken steps to address MMIW after outcries, but their attempts have not gone very far. Both organizations have missed the deadline for Savanna’s Act and the Not Invisible Act. These acts are to not only discuss the missing and murdered Indigenous women, but to also decrease these numbers.

The Not Invisible Act aims to boost cooperation to combat the MMIW epidemic, while Savanna’s Act demands the Department of Justice to improve training, coordination, and data collecting in MMIW cases.

Fartun Ahmed is a senior at CHHS and the Opinion Editor for the Heights Herald. She is a part of College Possible, National Honors Society and regularly...