Diversity in the medical field stays stagnant despite strides for equality

The untimely passings of many people of color can often be traced back to a white physician or doctor, raising questions about what diversity means in the medical field.

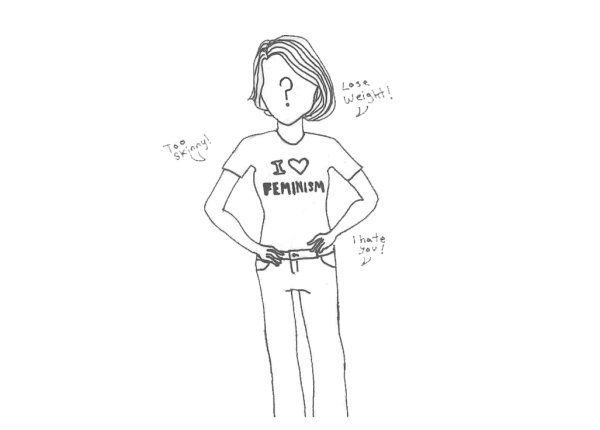

What do you imagine when someone says “doctor”? Let me take a guess: An old white male in a white coat. Statistically, you’re correct. This shouldn’t be surprising as throughout U.S. history, minorities have been suppressed in the workforce and beyond time after time, including in the medical field. But with such a diverse population ranging from diverse religions, races and ethnicities to sexualities and gender identities, does it make sense to have the typical cis white heterosexual male as the most common representation in the medical field?

Preference to white males in the healthcare system has brought many issues regarding patient care and health. Lack of understanding and trust creates a barrier in which, many times, leads to a patient’s refusal of services—especially when the services seem invasive. In the U.S., racial and ethnic minorities, and in particular, Black patients, have a higher rate of developing chronic diseases as well as premature death compared to their white counterparts. A crucial example of the widest racial disparities in women’s health is childbirth — Black women are 3-4 times (243%) more likely to die from pregnancy or childbirth-related causes compared to white mothers. Black men, out of all the demographic groups, have the lowest life expectancy. There are many factors that contribute to life expectancy, but the lack of diversity within practicing physicians seems to play a role.

In addition, consistent historical abuse by medical researchers and physicians towards minorities has created mistrust in the medical field — a mistrust largely seen in African-American males after the U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee. The Tuskegee experiment began in 1932; it was meant to find treatments for syphilis—a contagious venereal disease. Six hundred African American males were recruited with the promise of free health care. Although the participants were monitored by health workers, they were only given placebos (i.e. aspirin) despite penicillin being the recommended medication for syphilis. The ineffective care that the researchers provided led to death, blindness, insanity and other severe medical problems among the participants. The study was forced to shut down in 1972 due to public outrage and its unethical nature.

In a study conducted in 1995 by the University of Maryland School of Medicine and Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, it was found that minority patients were four times more likely to receive medical assistance by non-white physicians. Furthermore, physicians of color were more likely to treat minority patients as well as practice in underserved communities, as a majority of physicians have a passion to try to help their own communities.

In another study conducted by the National Bureau of Economic Research, it was concluded that patients are more likely to feel comfortable and validated being treated by physicians that, in many ways, have been or are currently going through the same struggles as a minority themselves. The problem, however, is the number of those physicians, with the Association of American Medical Colleges reporting in 2018 that 56.2% of physicians were white, 17.1% Asian, 13.7% “unknown,” 5.8% Hispanic, 5.0% Black or African-American, 1.0% multiple race, non-Hispanic, 0.8% other and 0.3% American Indian or Alaska Native.

So, how can we fix this? Honestly, there’s no single “fix”. Creating an environment where a diverse population feels secure during their most vulnerable moments in life is difficult. However, it all starts with pushing the importance of diversity. Inspiring young and talented minorities that are willing to commit to the hardships of working in the medical field is one of the key elements in creating a change. Through this, physicians’ and other medical workers’ communities will begin to build some trust in the system that has let them down time after time throughout history. As many professionals say, “the patient’s health is what matters the most.”

Valerie Barrera is a senior at CHHS and a staff writer for The Heights Herald. She is very passionate about writing and bringing people news about entertainment....

Sol Schindler is a senior at CHHS and is the A&E Editor and lead cartoonist of The Heights Herald. He is in the National Honors Society, Student Council,...